The African-American neighborhood of Fort Myers in an undated photo.

May 24, 2024 by David Silverberg

This is a revised and updated version of an article first posted on May 22, 2019.

This Saturday, May 25th, marks 100 years since two African-American teenagers were seized by a white mob and lynched in Fort Myers, Fla.

The anniversary comes amidst a rise in hatred and racism in the United States and serves as a stark reminder of where bigotry ultimately leads. It’s also a demonstration of what happens when the rule of law breaks down.

It can happen here—and it has.

It’s also worth remembering; history does not have to repeat.

What happened

This account draws from two sources: One is an article in The Fort Myers News-Press on the event’s 90th anniversary. That article, “Lynching history spurs call for closure, 90 years later” by reporter Janine Zeitlin, was published on May 21, 2014. The account drew on people’s recollections and the work of Nina Denson-Rogers, historian of the Lee County Black History Society, who pieced together fragmentary information on the incident.

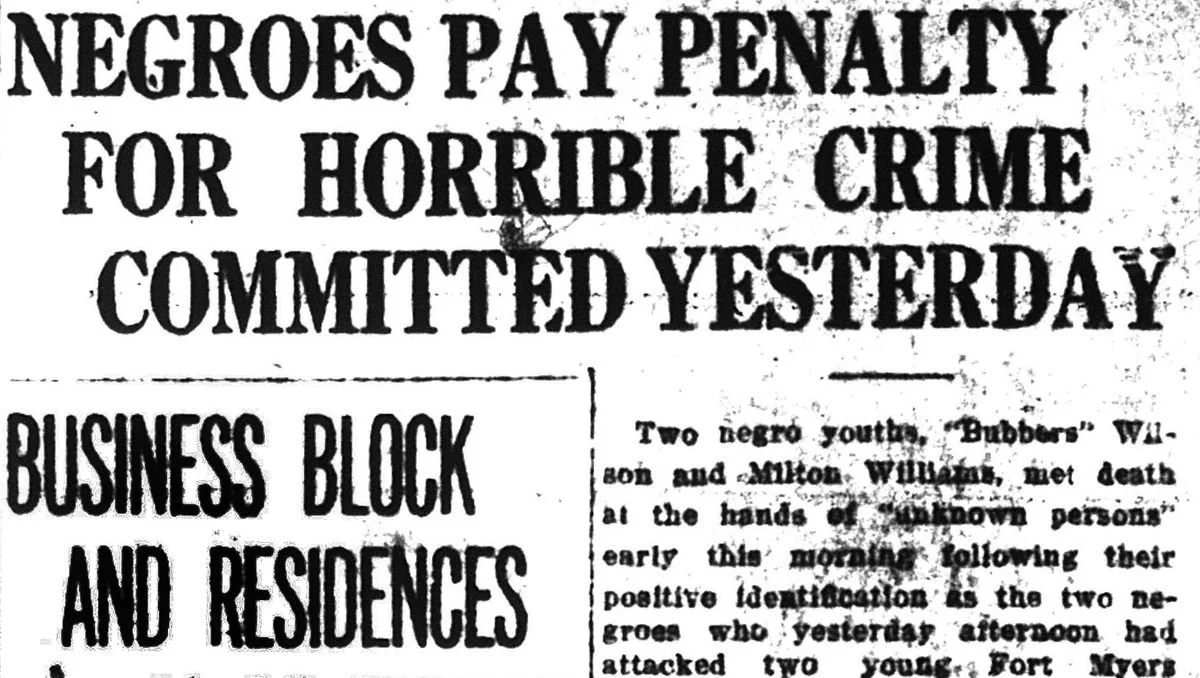

The other is the original, unbylined article that appeared in the Fort Myers Press on May 26, 1924, headlined, “Negroes pay penalty for horrible crime committed yesterday.” (Referred in this article as the “1924 account.” The article is posted in full below.)

According to Zeitlin, on Sunday, May 25, 1924 two black teenagers, R.J. Johnson, 14, and Milton Wilson, 15, (his name also given as “Bubbers” Wilson and the other victim is named as Milton Williams in the 1924 account) were spotted by a passerby swimming with two white girls on the outskirts of Fort Myers, then a segregated city of about 3,600 people. Lee County was home to about 15,000 people.

“The lynchings happened after R.J. and Milton went swimming at a pond with two white girls on the outskirts of town,” according to the Zeitlin article. “They were said to friends with the girls, maybe more. Perhaps they were skinny-dipping. There were rumors of rape, though one girl and her brother denied it.

“The two boys and girls lived near each other, were long familiar and played with each other as children, states Zeitlin. The swimming was reported by someone as a rape. The 1924 account simply states that the boys “attacked two young Fort Myers school girls.”

The black community first learned that something was amiss when evening church services were canceled. Just before sunset the rape report resulted in white residents on foot, horseback and in cars gathering at a white girl’s residence. From there they began invading black homes and yards in a search for the two boys.

During the evening, chaos spread through the city as the search continued. At one point a gas truck was driven into the black community with the intention of burning it down if the boys weren’t found.

Lee County Sheriff J. "Ed" Albritton in an undated photo. (LCSO)

At some point R.J. Johnson was found. According to the 1924 account, he was arrested by Sheriff J.E. Albritton and put in the county jail.

“Hearing of this the armed citizens went to the jail and demanded the prisoner. The request being lawfully refused by the sheriff, he was overpowered, the jail unlocked and the negro led out,” states the 1924 article.

According to that article, once seized, Johnson was “taken before one of the girls” where he was identified and confessed. According to Zeitlin, however, one of the girls and her brother denied that there had been any rape.

In the Zeitlin account, Johnson was taken to a tree along Edison Avenue, hanged and shot. According to the 1924 account “his body was riddled with bullets and dragged through the streets to the Safety Hill section.

“The search then continued for Wilson, who was found at 4:46 am the next morning by a railroad foreman, hiding in a railroad box car on a northbound train. He was taken from the box car, hanged, castrated and shot multiple times. His body was then dragged down Cranford Avenue by a Model T.”

"It was like a parade, some evil parade in Hell," according to Mary Ware, a resident who was quoted in a 1976 article in the News-Press. The crowd broke up when the sheriff and a judge appeared.

The headline in the Fort Myers Press.

On Monday the afternoon edition of the Fort Myers Press was headlined “Negroes Pay Penalty for Horrible Crime Committed Yesterday.”

On the same day a jury convened and absolved the sheriff, attributing the lynchings to “parties unknown.”

“That the rape had taken place, the black community definitely felt never occurred, that it was prefabricated by this white man who came across them swimming,” said resident Jacob Johnson in a late 1990s interview with the Lee County Black History Society, quoted by Zeitlin. “Everyone felt ... these boys had just been killed for no reason, other than they were there with these white girls.”

Commentary: Learning from history

Lynching is defined as any extrajudicial killing.

In the United States, however, it evokes a particular idea: a racially-based, mob-conducted, illegal, unpunished hanging driven by hatred, prejudice and rage, usually based on unfounded accusations.

The era of American lynching is considered to have lasted from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, often known as the Jim Crow era. If one wishes to put specific dates on it, it arguably lasted from the Plessy vs. Ferguson Supreme Court decision of 1896 that enshrined segregation of the races as “separate but equal” to 1954’s Brown vs. Board of Education when the Supreme Court ended segregation in education.

But these are debatable dates. There were lynchings before these dates and after. They didn’t all involve hanging.

What’s more, not all lynchings were racially motivated. In the western United States, cattle rustlers and other accused criminals were strung up by posses on the spot regardless of their race.

When it came to racial lynchings, according to one count, A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930, Florida had the highest per capita instance of lynchings of any state during the years studied: 79.8 victims per 100,000 people.

The Fort Myers lynching was just one of these.

Whatever the dates or history, it’s clear that lynching is where racism, blind fury and bigotry lead, the Fort Myers lynching no less than any other.

But the Fort Myers lynching is also a lesson on the rule of law. In 1924 the two accused teenagers had no rights, no protections, and no defense. They were never able to assert or prove their innocence. They were presumed guilty from the outset, never tried and were punished according to the whims of the mob.

As the rule of law is eroded in this country, every American loses the protections that law provides. The result can be something like a lynching—and can lead to the deaths of innocent people.

A century may seem like a long time ago, in a different age and this kind of behavior may seem ancient and unthinkable today. But the fury and hatred that led to lynchings is still very much with us.

Very recently, in our own time, on Jan. 6, 2021 an incited horde of insurrectionists invaded the United States Capitol. Outside was a crude gallows. Inside those imposing halls the screaming rioters demanded to hang the Vice President of the United States.

That was a lynch mob just as surely as the one that demanded the deaths of Bubbers Wilson and RJ Johnson.

In 1924, the mob succeeded. In 2021 it failed.

Even now, the only thing standing between mob mayhem and civilization is the rule of law and the willingness to apply, assert and enforce that law. It’s a precious gift that’s under enormous threat.

And if there’s any lesson that the Fort Myers lynching can teach, it’s that the rule of law needs to be defended as much today as it did then, 100 years ago—and it is just as threatened.

The gallows erected outside the US Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Tyler Merbler)

The full front page of the Fort Myers Press on May 26, 1924.

Below is the full text, with original capitalization and usage, of the article on the Fort Myers lynchings as published on the front page of The Fort Myers Press, on May 26, 1924:

NEGROES PAY PENALTY FOR HORRIBLE CRIME COMMITTED YESTERDAY

Two negro youths, “Bubbers” Wilson and Milton Williams, met death at the hands of “unknown persons” early this morning following their positive identification as the two negroes who yesterday afternoon had attacked two young Fort Myers school girls.

Within a few hours after word of the happening had reached town a systematic search was started independent of the efforts of Sheriff J.E. Albritton who with his force was on the job immediately upon hearing of the crime.

A general round up of suspicious characters by the sheriff’s office netted Wilson, who was lodged in the county jail.

Hearing of this the armed citizens went to the jail and demanded the prisoner. The request being lawfully refused by the sheriff, he was overpowered, the jail unlocked and the negro led out.

Taken before one of the girls he was identified by her and then taken away where he confessed to his captors, following which his body was riddled with bullets and dragged through the streets to the Safety Hill section.

The search for his accomplice was then carried out with increased vigor, all outlets from the city being carefully guarded. The hunted man was located about 4:46 a.m., on a north-bound train pulling out of the railroad yards. Following his positive identification, he met the same fate as the first negro.

The following jurors were sworn in by County Judge N.G. Stout, coroner ex-officio, this morning: C. J. Stubbs, C.C. Pursley, Vernon Wilderquist, Alvin Gorton, W.W. White and Thomas J. Evans.

Charged with ascertaining by what means the two negroes met their deaths, the jurors reported as follows: “the said “Bubbers” Wilson and Wilton Williams came to their death in the following manner, to-wit:

By the hands of parties unknown, and we herewith wish to commend the Sheriff and his entire force for the earnest efforts made by them, in their attempt to carry out the duties of their office.”

# # #

Liberty lives in light

© 2024 by David Silverberg